Why Consent is Better than Consensus

How to Involve Others in a Decision Without Getting Stuck

How to Involve Others in a Decision Without Getting Stuck

If you’re learning any sort of self-management practice, or just trying to evolve the way you work with other people, then you have to address a fundamental tension of modern life: we like to make important decisions together, but rarely do we all agree on what the final decision should be.

So, while we know that endlessly seeking agreement creates painful decision-making gridlock, it’s equally painful to disempower important voices just for the sake of decision-making efficiency. This is true of business relationships, but also interpersonal relationships.

Given this, we’ve become comfortable settling for far less clarity than we really want. And worse, this compromise usually doesn’t work, because inevitably, some people will still feel shut-out of the decision making process, and some important decisions will still take too long (if they get made at all).

So, how do we resolve this inherent dilemma of working with other people? I think the solution is to make a clear and rigid distinction between consensus (needing agreement) and consent (needing permission). And, as a standard for group decision-making, to generally seek consent rather than consensus.

Note: This distinction is fundamental to understanding the Holacracy® governance meeting process, but it has implications far beyond that.

To understand why consent tends to work better than consensus, you have to understand the following:

The word, “consensus,” means everyone agrees on something. A flock of birds, generally, has a consensus about where they are flying. Or, if most experts agree that a particular movie is good, then one could say there is a general “consensus” about its quality; i.e. general agreement.

“Consent,” in contrast to consensus, is really about permission. When you consent to something you permit or allow it. Therefore, consent usually pertains to what someone else wants; i.e. it’s not necessarily something you want. For example, a student might ask a teacher for consent to go use the bathroom, but the student wouldn’t ask for the teacher’s agreement (i.e. consensus). This means that consent is a helpful distinction for anyone who cares about personal responsibility and managing healthy boundaries.

More specifically, when you give your consent/permission to something, it means that you don’t see any, “harm” with the proposed action. If someone asks, “Is it okay to post our group photo on social media?” they are really asking if there is any reason why I think posting the photo would negatively impact me in some way.

If they asked me if I agreed with the decision, that requires a completely different headspace. I’d have to consider something akin to, “even if they weren’t going to do it, I would still want to do it myself.”

And of course, sometimes that’s not a relevant distinction. Sometimes it doesn’t matter. But my point is…sometimes it does. And if you don’t have the distinction, you won’t be able to tell the difference.

Note: For anyone familiar with Holacracy practice: permission = I don’t think there is harm = “no objection.”

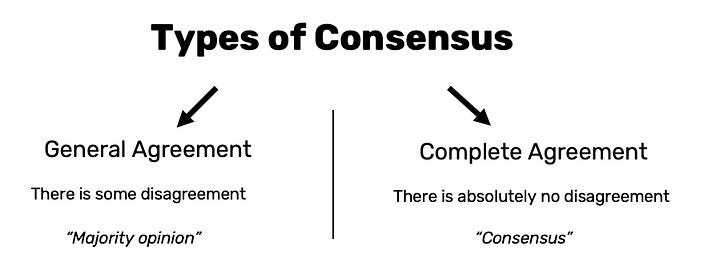

There is an important distinction between, 1) a majority generally agreeing about something (i.e. there still may be disagreement), and, 2) everyone fully and completely agrees to the same thing (i.e. there is no disagreement).

General Agreement: In English, “consensus,” means, “general agreement.” And if you really pay attention, you’ll hear things in the media like, “Amongst the fanbase there is a consensus that…” or, “There is an emerging consensus in the medical community that…” But I think this idea of “general consensus,” quickly confuses things when we use it as a standard for decision-making, because what we are usually trying to communicate by “general consensus,” is something like, “a majority opinion.”

Complete Agreement: Imagine six friends want to get together for dinner. There needs to be complete agreement (i.e. “consensus”) among them on where and when to go. If they want to achieve the goal of eating together, there can no ZERO disagreement. “Consensus,” is a good word to use for this (or it was and I’d like to reclaim it) because even though it’s rare, sometimes you need it.

With that said, a leader might prefer the word, “consensus,” because it seems to convey an overall feeling of cohesiveness or alignment that the term, “majority opinion” lacks. Fair enough. But even in that case, I think they could bring more honesty and consciousness to their intention if they explicitly called it something like, “alignment” instead.

By definition, whenever we are seeking general agreement, or a “general consensus,” we should be conscious of the fact that we’re OK with some opinions being excluded.

The fact is general consensus means some individuals must sacrifice their own needs or opinions in service of the greater good. And we’re usually fine with that reality, because we all know that sometimes it’s the only way to move things forward, especially with a larger group (and even more especially if the decision-making authorities are unclear). My point isn’t that this is bad, but simply to highlight once again that there is in fact a downside to calling this, “consensus,” when it would be more honest to call it, “majority opinion.”

And on the other hand, while complete buy-in and agreement (i.e. “complete consensus”) is way better for making sure everyone is getting their needs met and everyone feels fully engaged, there is usually no practical way to use that as a meaningful threshold for a group of any notable size or diversity. It’s probably why we’ve settled colloquially on a practical definition of “consensus” as “generally agree,” because we know that some people are just going to have to suck it up for the sake of the group.

Given this, I think leaders tend to make a show of broadly and vaguely seeking consensus, but without actually requiring it (let’s call this “consensus theatre”). And they do this because the decision-making authorities are unclear, or don’t know of another way to move things forward. So, they invest their time socializing decisions before they enact them, and then working to repair the relationships with those people who are alienated by the process.

I started off this article by talking about how hard it is to balance getting people involved with actually moving things forward. Then, I said that consensus is high on collaboration, but low on decision-making speed, while the inverse is true for consent.

While all of that is broadly true, I left out an important nuance; because it’s equally true to say something like, “In practice, consent is also very collaborative because it requires permission from everyone. So, it’s a lower standard than agreement, but since you must get it from everyone, not just a majority, you’re not leaving any of those important voices out.”

At least this is what I’ve experienced in practice. My theory for why consent, the lower threshold, seems more collaborative than consensus, is that consensus is just too damn idealistic. And by aiming for something you can’t reasonably achieve, you’re actually signing up for a much lower, and less clear standard (which I called, “general consensus”).

So, is consent a lower standard than consensus? Yes and no. But either way, when you make the standard explicit, even if only in your own mind, you give yourself more choices; i.e. “Do you need agreement on this thing, or do you just want to know if they have any objections?”

Of course, when it comes to language there is no such thing as perfect clarity, and within different groups or cultures, rules will vary, but I feel confident in asserting (at least to an English-speaking audience) that most people, if asked for something, would NOT use a phrase like, “Yes, I consent to that.” It doesn’t exactly role off the tongue.

But it’s a useful distinction for navigating interactions or responding to a request if there is some ambiguity, so we don’t want to lose the concept, even if we don’t often use the word. And in practice, I’ve found that a good way to communicate the concept of consent is to say, “no objection.”

So, if someone asked, “Shall we play some music while we work?” and you weren’t particularly interested in listening to it, but it wouldn’t really bother you either, you could say, “No objection…go for it.”

Or, if you wanted to organize a supply closet, rather than vaguely asking a potentially impacted person, “What do you think about me organized the supply closet?” you could ask, “Any objection to me organized the supply closet?”

Of course, real human interactions usually sound something like, “Hey…you mind if I do this?” and, “Yeah, sure.” With that said, even words like, “consensus,” “agreement,” or, “permission,” though rare, but usually unremarkable. So, if you’re thinking, “Well, ‘no objection’ sounds really weird…” I understand. So, if you have a better word, go for it. Just don’t lose the distinction.

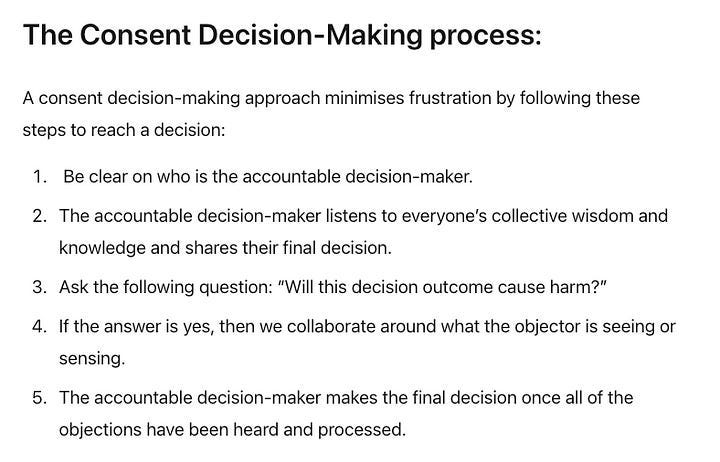

At the group or organization level, consent can be baked-in as a safety check for certain types of decisions. Meaning, “consent is better than consensus,” doesn’t just have to be a rule-of-thumb you apply occasionally.

This kind of process requires some facilitation experience or expertise, so they aren’t the kind of thing I would recommend for most operational decisions (for more on why this is, see here). But if there is a particular sticky issue, with lots of stakeholders, then a consent-based process is often the best way to go.

Not only do you tend to move things forward, but from what I’ve seen, people tend to be much more accepting of a decision or outcome they don’t particularly like (i.e. they did not “agree” with it, but had no objection to it), when they feel like they can trust the process used to get there.

Note: Of course you could also bake-in consensus processes (e.g. “Policy: No one may hire a new partner unless all current partners agree”).

Finally, let me restate that there’s nothing objectively wrong with seeking consensus. You need consensus from a group if you’re all planning on being in the same place at the same time. But it’s waaaaaaaay over-used.

We took a word, “consensus,” which is fine for describing the majority opinion of a group, and unconsciously started applying it as a standard for decision-making. Let’s reclaim it. And then add the phrase, “no objection,” because in practice, seeking consent is often more practical and more collaborative.

To learn more about self-management, join a community of pioneers and check out our e-courses → Self-Management Accelerator