Understanding Relational Agreements

Relational agreements are like any form of liberating structure. They impose order on something not to restrict it, but to allow it to more fully flourish.

Relational agreements are like any form of liberating structure. They impose order on something not to restrict it, but to allow it to more fully flourish.

Introduced in Holacracy Constitution v5, rules about “relational agreements” were added as a complement to governance. This made some things more clear, but also introduced some complexity.

But before I say too much about them, I need to introduce a presupposition that I’ll also emphasize several times through the article; if you don’t need an explicit agreement with someone, don’t artificially pursue one.

Just like with governance, if things are working well as they are, leave them alone. Relational agreements should be tension-driven. Now, let’s get into the details.

Practically speaking, relational agreements aren’t just a specialized tool for a specialized job, they are actually three different specialized tools for three different specialized jobs:

I’ve found that these differences make it extremely challenging to speak coherently about all three types simultaneously. Several points of emphasis I want to make about the first two types, are, practically-speaking, untrue of the third. Therefore, this article will focus on the first two types, and I’ll publish another article specifically about relational agreements and employment contracts.

Here is a summary of what you need to know:

In addition to the above points, I’ve added a bonus section:

6. Frequently Asked Questions:

Although not technical-sounding, the term “relational agreement” has a specific definition in the Holacracy Constitution.

Article 2 of the Holacracy Constitution v5.0 details the “Rules of Cooperation” for partners in the organization, which includes the section on what relational agreements are and how they are supposed to work. Let’s start with what the constitution actually says:

As a Partner, you may have “Relational Agreements” with other Partners. These are agreements about how you will relate together while working in the Organization, or about how you will fulfill your general functions as Partners of the Organization. They may add to or clarify the duties in this Article, but they may not conflict with them.

Relational Agreements must remain focused on shaping behaviors that generally underpin work; they may not set expectations of work to do in a Role, nor expectations about how a Partner will prioritize across different Roles. Further, they may only specify concrete acts to do or behavioral constraints to honor; they may not include promises to achieve specific outcomes or embody abstract qualities.

As a Partner, you may request a Relational Agreement of another Partner for your own personal preferences or to serve a Role you fill. That Partner may accept or reject the requested Relational Agreement based on their own personal preferences. Unless otherwise agreed, either party may later terminate the Relational Agreement by notifying the other party.

As a Partner, you have a duty to align your behavior with any written Relational Agreements you have made. Anyone facilitating a meeting or process for the Organization may also enforce these Relational Agreements during that meeting or process, as long as they don’t conflict with anything defined in this Constitution.

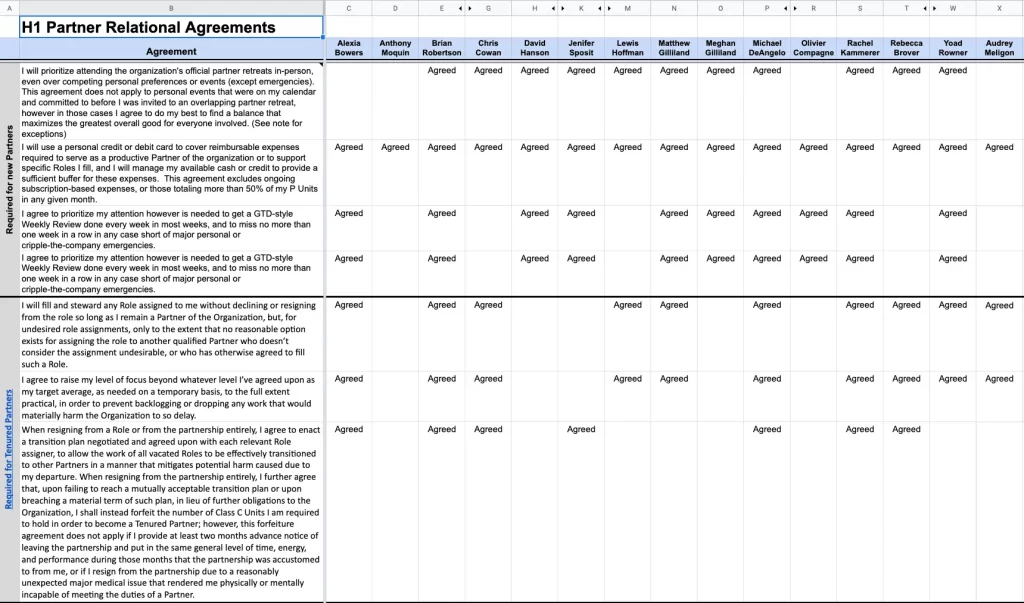

There is a lot to unpack, so let’s look at each of the important elements one-at-a-time. But to give you some clarity as we begin, here are some real examples of what a Holacracy-style relational agreement looks like:

Now, two quick notes about these examples. First, I’m not necessarily saying these are good relational agreements — just that they meet the Holacracy definition.

Second, these real examples were created to provide clarity within actual relationships to resolve actual tensions. I’m only sharing them to convey the proper energy and focus of a relational agreement, and not to suggest that these specific agreements are somehow objectively or universally helpful. If you don’t need an explicit agreement with someone, don’t artificially pursue one.

Generally speaking, relational agreements are about the people, not the roles.

The governance records of your organization directly capture the expectations, authorities, and restrictions that apply to the work of the organization. So, an accountability like “Updating the company’s website” for a Webmaster role defines an expected activity, but it doesn’t say anything about the role-filler’s personal behavior.

So, what do you do if the Webmaster role-filler doesn’t respond to your text messages? Or, what if Kevin is always late to meetings? It’s not just about a single role he is filling; it’s a personal behavior that impacts all of his roles.

Governance isn’t a good tool for resolving these tensions, and this is where pursuing a relational agreement may help. While relational agreements can’t be used to set prioritizations or make promises to achieve certain outcomes, they can be used to help people resolve interpersonal conflicts by exploring and defining concrete behaviors to improve our working relationships.

And if you’re thinking, “Well, why not just go talk to them about it directly?” then you’re on the right path: Talking with people directly about their behavior is often the best option, even though Holacracy’s rules say nothing about how to make that conversation happen (though I’ll share some best practices in the FAQ).

In addition, if you’ve tried the direct feedback approach you may know how easily these conversations can blow up in your face. This is where a relational agreement (or the pursuit of one) might help.

Relational agreements must be focused on shaping concrete behaviors, not requiring someone to adhere to an abstract principle.

This topic deserves its own article, because there is a principle here which is generally applicable to all of Holacracy practice: the distinction between principles (abstract qualities) and practices (concrete behaviors).

And it’s a distinction we usually don’t need to make. Parents instruct their children to “be nice.” A romantic partner may request “feeling loved” by the other person. But as natural as these might be to say, they are usually not very helpful to hear.

The problem with asking someone to adhere to a principle like “be nice” is that it doesn’t give the kind of clarity someone needs to reasonably fulfill their agreement. How would you know someone was nice? What observable behavior would tell you one way or another?

Principles work well as heuristics to help an individual subjectively interpret and apply. But if I want someone else to agree to something, and I want them to help me meet my need, the more concretely it is described, the better.

Of course, just like governance, there is no such thing as perfect clarity or perfect concreteness. It’s a spectrum; use what makes sense to you. But just to drive the point home, here are some real-life examples to help illustrate the difference and give you a sense of why defining a concrete behavior often works better:

Of course, defining a satisfactory concrete behavior usually isn’t easy. But that’s the point. Doing the hard work of clarifying now, improves your chances of making things better going forward. And again, remember: if you don’t need an explicit agreement with someone, don’t artificially pursue one.

Relational agreements can only be requested, not demanded.

Relational agreements should only be voluntary. And much like the previous point about abstract principles vs. concrete behaviors, there is a spectrum of requests vs. demands, but one on which we can make some meaningful and non-obvious distinctions.

Note: And if you’re wondering how agreements “required” by the organization can still be considered requested not demanded, follow me on Medium so you won’t miss the next post.

The best definition I found for the difference comes from Marshall Rosenberg, pioneer of Nonviolent Communication who says, essentially, if you feel upset when someone turns down your request, then it wasn’t actually a request; it was a subtle demand.

This is a big deal, because one of the reasons relational agreements were added to the Constitution was to reinforce the principle that people are only responsible for what they have consciously agreed to.

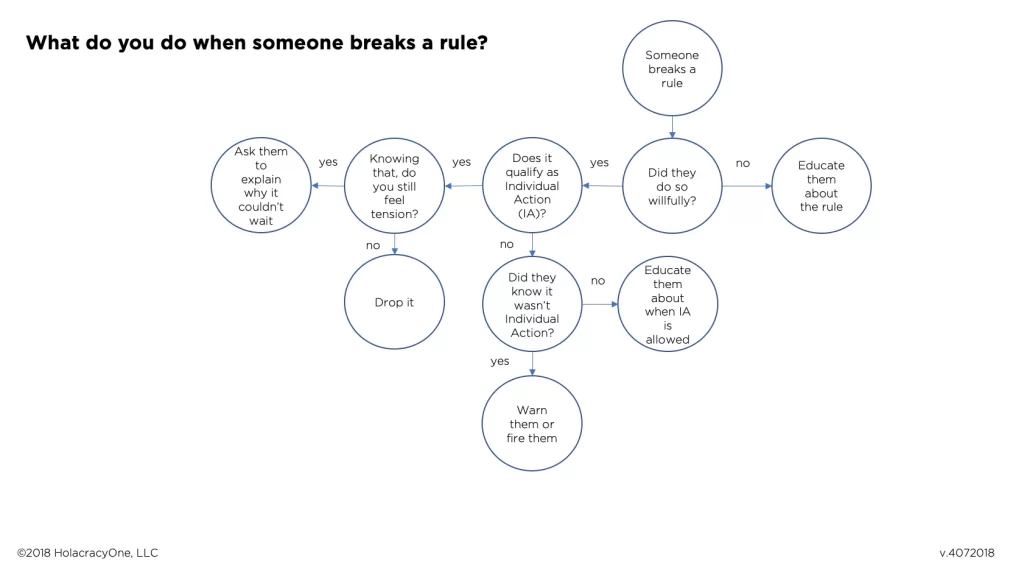

So, what do you do if someone is annoying you ? Imagine that they make a mess of the microwave in the break room and never clean it up, or that they talk too loudly on the phone. Do you just request that they stop? Well, yes.

But of course, how you ask matters. And most of us don’t intuitively make requests in ways that make it easy for others to help us.

In the absence of guidance about HOW to explore, request, or renegotiate a relational agreement, there are two meta-agreements which can be particularly helpful.

In a way, we’ve come to the end of what the Holacracy Constitution tells us about relational agreements. It defines them, but that’s about it. In other words, it doesn’t say much about how these agreements should be enacted.

Meaning, some of the most interesting questions around the process of requesting or updating agreements are left unspecified.

In the absence of rules about the process-side of relational agreements, I’ll do my best to try and answer specific process questions in the FAQ. But first, I want to share two meta-agreements (i.e. they are themselves just relational agreements), which I think provide a simple and effective-enough foundation. They are:

Now, I could say a lot about the reasoning behind these agreements, but hopefully it’s self-evident. I feel confident in saying that from my experience, these more-or-less capture the implicit expectations around how relational agreements get enacted in healthy environments.

With that said, these agreements are just that. They don’t really provide any meaty details, and the details around this stuff are really important. For those who are interested, the following section will hopefully provide some additional clarity.

Note: I’ll do my best to try and answer some common questions, but first I want to clear that we’re moving beyond explicit constitutional rules here and into some personal recommendations. And of course please refer to specific methodologies like Nonviolent Communication, Systems-Centered Therapy, or MetaRelating for more expert details.

I’ve come across a few criteria, but remember: anything that moves things forward is good.

Relational agreements aren’t just a specialized tool for a specialized job; they are actually three different specialized tools for three different specialized jobs.

And I haven’t been able to cover them in nearly the amount of detail they deserve, especially when it comes to required agreements, so make sure you follow me on Medium to get the latest articles.

Again, some people get the impression that relational agreements are intended to legislate away all of the real feeling and juice and heart out of a relationship, but that’s not true.

Like governance, relational agreements are a form of liberating structure, meaning they impose order on something not to restrict it, but to allow it to more fully flourish. Just as lines on a highway allow everyone to get to where they want to go faster and more safely, just think of relational agreements as a way for us to meaningfully make each other’s lives more wonderful.

Join me on the Holacracy Community of Practice.

Read “Introducing the Holacracy Practitioner Guide” to find more articles.

To learn more about self-management, join a community of pioneers and check out our e-courses → Self-Management Accelerator