Holacracy Basics: Understanding Purpose

Holacracy Practitioner’s Guide

Holacracy Practitioner’s Guide

In Holacracy, purpose means “a capacity, potential, or goal that the Role will pursue or express on behalf of the Organization (§ 1.1a).”

And here are some examples…

They are all fairly short and punchy. They have flair. And unlike an accountability — which, by comparison, is much more specific — a purpose isn’t clearly actionable and leaves a lot to the imagination.

But before I get into details, let’s take a step back a bit and ask: what’s the purpose of defining a purpose? Why should we write it down in the first place?

According to Tim Kelley, founder of the True Purpose Institute and author of the book True Purpose, there are a few situations in which writing down an explicit purpose is a good idea. First, if you’re dealing with a long time-horizon with lots of complexity, then writing down your overall purpose may be a good idea. That’s because, on its own, intuition isn’t a good clarifier. The whole reason something is confusing is because you feel conflicting intuitions about it.

Second, having defined purpose statements is really useful when you’re working with other people. If I was working alone, then an explicitly defined purpose would only help me. I’d be the only customer. But in a self-organizing practice, we need to have autonomy and alignment. Because we work together, my concerns aren’t limited to my own personal intuition and how I feel about a given purpose; they include a shared purpose. And if we don’t define an explicit purpose, we’re likely to fall back into an unconscious one, which tends to be some variation of, “Make everyone happy.”

Defining an explicit purpose isn’t about trying to predict and control the future. Members of the organization are invited to listen to what the organization wants to become; what purpose it wants to serve. And we can’t know what that is unless we talk about it.

So, that’s why Holacracy practice puts so much emphasis on having an explicit versus intuitive purpose. But that still doesn’t answer the question of when you should use it.

A role or circle is not required to have a defined purpose. As long as it has at least one accountability or domain, then no defined purpose is needed (in which case you can use the role name as a de facto purpose).

When should you use a defined purpose statement, and when can you safely leave it blank? I’ve come across a few cases.

Accountabilities, like all governance, evolve over time. Parts get added. Tweaked. Removed. Re-added. Sometimes a role ends up with too many accountabilities, or the accountabilities are becoming overly specific or too long. And sometimes, the one-tension-at-a-time approach ends up creating a fractured collection of expectations that, in the role-filler’s interpretation, don’t add up to anything cohesive.

In these cases, it often makes sense to add a purpose, re-factor the accountabilities to reduce their complexity, and help orient a role-filler with a clearer sense of what they are ultimately trying to achieve.

Sometimes that aspirational purpose has gotten out of hand. There is a role or circle with a purpose that’s too big. Again, there is no objective definition here, only the tensions that have surfaced (usually surfaced from a Lead Link/Circle Lead or a role from a broader circle).

Maybe the Blogger role is taking on too much — writing and writing and writing about any subject vaguely related to the company’s industry. Upon investigation, the role-filler points out that their role actually has the purpose, “Publish everything you can.” Well, touché.

In fact, good job! They’ve been absolutely crushing their role’s purpose. We can assume at one point that the purpose statement was an improvement. But now a new tension has surfaced, and the scope of that role’s work needs to be scaled back.

Sometimes a role-filler is rigidly focused only on their accountabilities, but you think they should consider a wider net of possibilities. Imagine a role-filler who is meeting all of the responsibilities of role-filling (Article 1.2), but they exhibit no real ownership over the role. Okay, fine. No inherent judgment on that. After all, they might not need to feel much ownership. But clarifying the purpose of a role might just stretch open a role-filler’s horizons and unleash their creativity.

Meaning, a role-filler should be using their role’s purpose as a guide as much as their accountabilities. For example, if someone requests that the Finance role take a project like “Financial reports are easy to understand,” they should check their current accountabilities. But they shouldn’t stop there. The Finance role’s purpose is equally relevant for determining whether or not a given project should fall to your role or not (and they should be honest and transparent if that answer is “No.”)

This is how you open up what the role consciously considers as part of its world. You increase its span or scope of care. That helps you deal with the issue of feeling like accountabilities aren’t cutting it.

Accountabilities are useful for defining any expected ongoing activities of the role (e.g. “Delivering services”). They tell your hands what to do, while purpose speaks to your heart; it defines what your role cares about.

A role-filler is always empowered to use their best judgment to fulfill the purpose of the role (even if the purpose is implicit), but that can leave a lot to the imagination. If the purpose answers the question, “Why does this role exist?” accountabilities answer, “How, specifically, should one go about achieving that purpose?”

But here’s the thing. Accountabilities aren’t giving all of the hows, only the ones that are needed. The ones others need to expect. Accountabilities don’t need to be exhaustive, precisely because you have a construct like purpose at your disposal.

Since both purpose and accountabilities define a role’s area of concern, practitioners can be forgiven for crafting purpose statements that sound like high-level accountabilities. For example, if a Programmer role is given the purpose “Writing and testing code,” that isn’t a why. It’s a what. Or a how.

With that said, an accountability-style purpose doesn’t cause that much harm. It doesn’t take advantage of the distinction, and it perhaps increases confusion, but it’s a minor problem.

However, if you notice an accountability-style purpose being proposed, raise an objection. For example, “Objection, NVGO…in my interpretation that purpose doesn’t meet the constitutional definition of a purpose which is a capacity or unrealizable goal.” Then you can fix it together in integration.

In the traditional management hierarchy, “purpose” is often identical to “mission” or “strategy.” But Holacracy practice breaks these down into a few separate things.

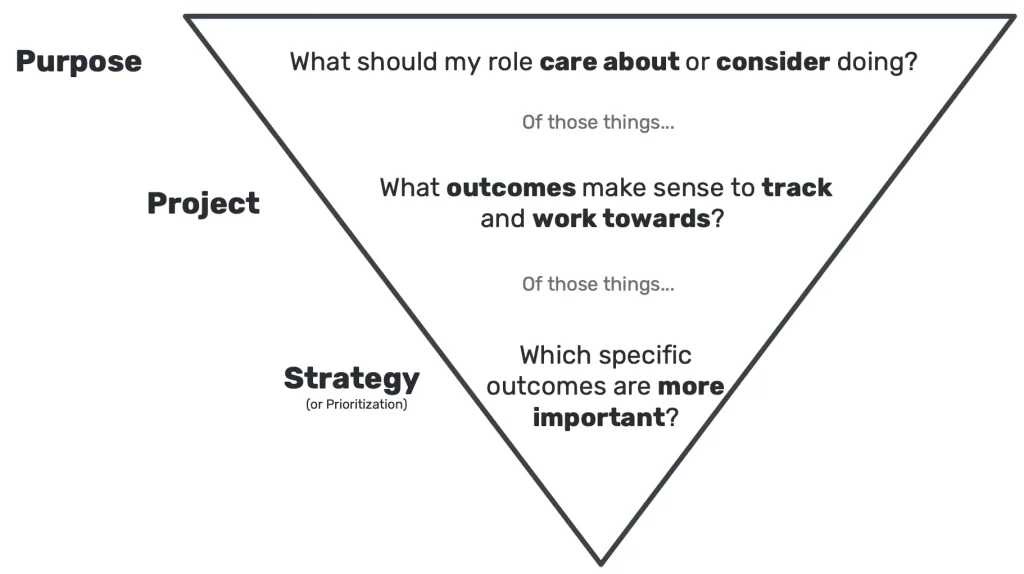

To simplify the distinction, let’s start by looking at a series of questions every role-filler should regularly ask themselves because each question has a corresponding construct.

Purpose helps you ask and answer this question. Purpose helps define a scope of concern, meaning it helps distinguish what I need to care about versus what you need to care about. If a decision needs to be made, and it’s not clear who should be making it, we can check our respective role purposes to untangle it.

Those are projects. A role accepts a project solely based upon whether, in the role-filler’s interpretation, that outcome fits within the scope of the role (defined by accountabilities and/or purpose). For example, “Supplies delivered to the conference location” is a project.

In Holacracy, a goal might be a project. The constitution defines a project as any outcome, a word intentionally missing the subtle sense of urgency or intention usually conveyed by a goal, but it’s pretty close (for more on projects in Holacracy, read this).

“New Business Launched” and “Filing cabinet re-arranged” are both projects. While one isn’t inherently a better project than the other, neither is a good role purpose. If there is something with a clearly defined end-point (i.e. a realizable goal), then it might be better as a project, not a purpose.

This is where a Holacracy-style strategy may come into play. It doesn’t mean the end state, outcome, goal, or destination — that would be better captured as a role purpose or project. Instead, a Holacracy strategy is a heuristic or rule-of-thumb that helps partners prioritize their work (i.e. prioritize this, not that).

Rather than define the destination itself, a strategy provides orientation, much like how a compass allows you to orient in a complex environment. For example, “Fast response even over complete response” is a Holacracy-style strategy (for more, read Understanding Strategies).

If your organization is just starting off with its Holacracy practice, then it helps to have some roles with explicitly defined purposes to introduce the construct. But don’t overdo it. You can sometimes find starting purpose statements in the conventional job description, like this one I recently found for a client in the education space: “Expanded learning opportunities for students.” That’s a fine start.

Or if you’ve been practicing for a while, but haven’t found many occasions to consider the defined purpose of a role or circle, maybe this article will give you a better sense of how to use them going forward.

Read “Introducing the Holacracy Practitioner’s Guide” to find more articles.

To learn more about self-management, join a community of pioneers and check out our e-courses → Self-Management Accelerator