Conducting a Holacracy Governance Audit

Identify Holacracy sustainability issues, but be very very very very careful.

Identify Holacracy sustainability issues, but be very very very very careful.

Reviewing an organization’s governance records in GlassFrog can help you identify Holacracy sustainability issues — stuff which, if you never identify it, could fester and cripple your Holacracy practice.

However, while it may be fun to stand back and critique, the audit can very easily be misused. So easily in fact, that I hesitated to share it publicly. On the other hand, we’re all adults, so if you pinky swear you’ll be careful, then we can proceed.

The reason this needs a warning is because it seems like an audit is about reviewing the quality of the governance, but this is deceptive. Because governance isn’t anything we need to optimize or improve just for the sake of improving. Unlike a conventional org chart, no one is responsible for designing the governance — governance is organic. It’s the result of many many many people processing many many many specific tensions over lots and lots and lots of time. All governance is imperfect and no one should convey that it shouldn’t be.

So, like performing surgery on the human body, we have to be very careful any time we artificially open things up and start poking around. So, let me crystal clear: The purpose is to identify Holacracy sustainability issues –NOT improve the organization’s structure.

In other words, this isn’t to improve accountabilities. Or create more clear connections between roles or circles. Nor is the audit about the content of the business itself. It’s only for identifying sustainability issues, the details of which are described in the next section.

Note: This thing called a “Governance audit,” is one way for an elected Facilitator to enact their accountability for “Auditing the meetings and records of Sub-Circles as needed.” But it’s just one example. Remember, Holacracy equals the constitution. So, consider this something like a best-practice as it was invented (and not by me) to help clients with their Holacracy adoption. I learned about it when I joined HolacracyOne and have just added my own distinctions and suggestions to it.

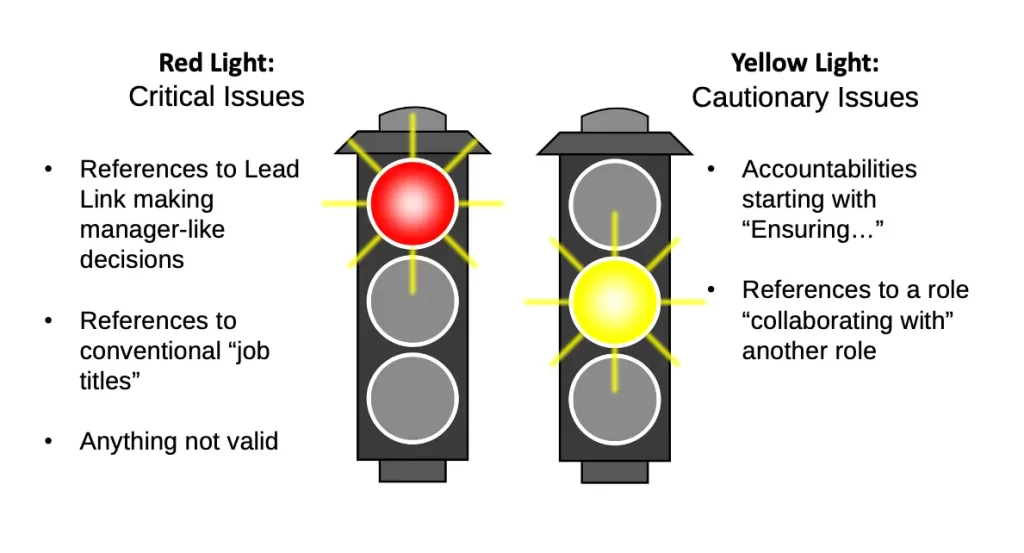

In the next section, I’ll go over the concrete steps to actually conduct the audit, let’s clarify what you’ll be looking for when you get there. And there are really two levels of importance; what we call Red Light, critical issues and Yellow Light, or cautionary issues. Here’s a diagram to give you the gist of what that priority means.

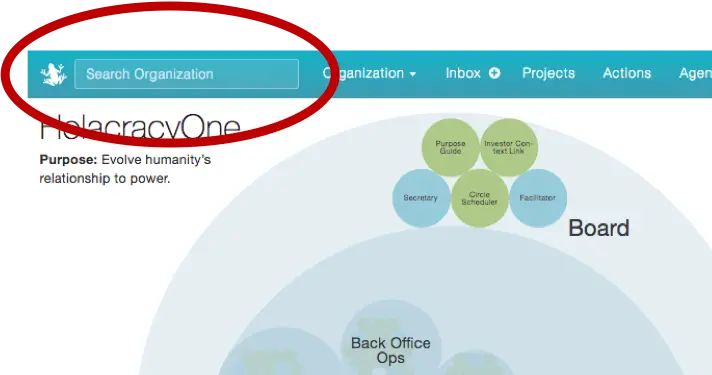

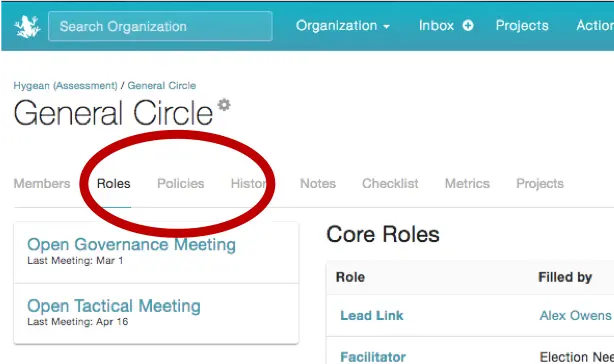

To conduct the audit, you’ll be making liberal use of GlassFrog’s “Search” feature. Currently, the search feature isn’t as intelligent as Google, and it’s quite literal. So, if you search “Lead Links,” it won’t show you any result for “Lead Link.” So always use the minimum stem; e.g. if you search for “Collab,” you’ll get all results for “Collaborating,” and “Collaboration.”

I recommend you systematically go through each of the following sections and use the search terms I suggest as guidance.

And make a record of the specific examples you come across (if any), to make it easier to share what you’ve found. Additionally, by restricting it only to concrete examples, you’ll avoid speaking in unhelpful and patronizing generalities (e.g. “Hey, I think we should do more with power shift.”)

Finally, I’d suggest sharing what you’ve found on the Holacracy Community of Practice (it’s free to join) if you want to get feedback.

Holacracy is about replacing the power-system at its core, and since the Lead Link role is most commonly filled by former managers, anything in governance which specifies a Lead Link’s involvement should be suspect.

SEARCH:

Remember, the Lead Link isn’t actually performing operational work of a circle, and ideally should only take up about 10% of a role-filler’s time. It’s also important to remember that the person filling the Lead Link role may need to be involved, but that involvement should be defined through other roles (e.g. roles like Operations Guru, or Accounting Advisor which capitalize on the individual’s wisdom and experience).

WHAT TO DO ABOUT IT:

Another key indicator that the old power structure is lurking around are references to conventional “titles” that work against the powershift (and may be invalid if there is no such role). For example, a “CEO” role, or a “Vice-President of Operations” role.

SEARCH:

A few more words of warning though. First, don’t be fooled into thinking that role names with the word, “Manager” or “Director,” are necessarily a problem, because a role name like, “Website Manager” is totally fine. I’ve also seen a role called, “Cruise Director,” who was responsible for planning social functions.

So, the question to ask yourself is, “Is it suggestive of a Manager or Director of people?” because that would be a problem. Again, the point of the audit is to get some transparency into things, not go on a witch hunt. Use your best judgement on what you think is worth digging into.

WHAT TO DO ABOUT IT:

Another Red Light issue to look into is anything invalid. Now, sure, this stuff should’ve been caught in the governance meeting because someone should have objected…but, hey…*shrug. It happens. Since governance isn’t written in stone, we can easily correct any issues, and there are a few easy-to-identify problem areas.

Policies can not demand action; just constrain or invite it should someone want to impact a domain (you can read more about policies here). To clarify, it would be invalid for a policy to say, “All roles must respond to customer emails,” because that is literally requiring action. Maybe something else was intended, but we are only interpreting what is written with as little inference or extrapolation as possible.

Contrast this with a policy like, “Any role negotiating with a customer, must respond to their emails.” This would be valid, because it’s not requiring action — you don’t need to do anything. That is, unless you’ve chosen to actively negotiate with a customer, in that case you must do the thing the policy requires (i.e. respond to their emails).

SEARCH:

WHAT TO DO ABOUT IT:

Oh boy. This is an important and nuanced issue, but since I’ve already published an article specifically about this, I’m just going to summarize.

These invalid policies usually look something like, “GCC Policy: All timesheets must be submitted by Thurs.” The reason this is invalid, put simply, is because the organization can only control what it owns (its roles and assets) and it doesn’t own people. It can make agreements with people, but it cannot unilaterally mandate or determine people’s behavior. So, policies that try to control people would be invalid.

Most often the issue is created when an old employee handbook is translated verbatim into governance. That’s better than NOT having it in governance and still expecting people to adhere to it, but it usually creates confusion.

SEARCH:

WHAT TO DO ABOUT IT:

Yellow Flag Stuff is often not as serious, but if left unaddressed, could further some misunderstandings which can hurt your Holacracy practice. It’s mostly about misusing the tool. It’s like watching someone try to drive a nail into a piece of wood using a stapler. It won’t be long before they walk away from the unfinished project thinking, “Staplers suck.”

Again, a warning: governance isn’t supposed to be perfect — it emerges from a group process of each individual processing a specific tension. So, the goal isn’t to improve the governance, so much as reduce the chance it’s harmful. And because some of these issues are a little more nuanced than Red Flag issues, I’ll explain why we think they’re important to identify.

While this isn’t as impactful as the power shift issues we discussed before, accountabilities or policies that require collaboration or coordination sometimes point to a different kind of power issue — consensus. Now, in general, these verbs are not great choices for accountabilities because they aren’t very clear, but on it’s own, that’s not such a big deal. Again, governance will never be perfect.

However, it is an issue for organizations in early practice for two reasons. First, some basic assumptions get confused. In Holacracy, anyone can take any action or make any decision in their role as long as it doesn’t break a rule — but when you have an accountability that requires you to collaborate, well who is going to make the decision? We have lost some clarity.

The second reason this is a problem is because it can have a snowball effect in early practice. Once you start putting accountabilities for “Collaborating with…” on roles, it suggests that any role without that accountability doesn’t need to collaborate (which isn’t true). It’s based on the common misunderstanding (taken from our conventional way of working), that we need to define everything in an accountability rather than leaving it up to the role-filler’s judgement. After all, the Secretary has the full authority to schedule the required meetings, and even though there is nothing in the accountabilities about “coordinating,” they usually do.

SEARCH:

Again, it’s possible these things are perfectly fine. If it’s more clear than things were before, then it’s a step forward. Meaning, don’t worry about isolated cases, one or two cases usually won’t cause a problem — but you do what to look for a pattern. That suggests there is a larger misunderstanding about how accountabilities work, and therefore how Holacracy works.

WHAT TO DO ABOUT IT:

Again, this isn’t about improving governance, it’s really about identifying important misunderstandings which, if left unaddressed, could cause more problems. Now, my business partner Olivier Compagne has already written a detailed post about how to deal with these, so I’m going to keep it short (you can read his thorough explanation here). He states,

Sometimes, these accountabilities convey an intent for the role to control the work of other roles, e.g., A Customer Service Lead with an accountability for “Ensuring that all Customer Service Agents provide a service of quality to customers.” The problem here is that this accountability is not achieving the intended goal: an accountability does *NOT* give any extra authority to control how another role does its work.

SEARCH:

WHAT TO DO ABOUT IT:

“To accomplish the intended effect, an alternative would be to propose adding an accountability on the Customer Service Agent role itself for “Responding to customers’ questions and helping them get what they need from our company, while offering the customer a positive experience of going through that process.” Then it’s up to the Lead Link of the circle to assess whether each person in that role is a good fit for the role — and to remove them from the role if they’re not.”

These aren’t really even Yellow Flag issues, but I wanted to highlight them to illustrate some of the other common misuses of governance. Again, governance is always tension-driven, so if no one feels tension about it, great. On the other hand, maybe there’s no tension because no one realizes there is a misunderstanding.

Some accountabilities are used to convey constraints on authority or strategic prioritization, when these could be more effectively conveyed via policies or strategies. For example:

Again, if you want to create restrictions on roles, use policies. If you want to create restrictions or set expectations for the people in the organization, refer to this article.

This could indicate that no tensions have arisen yet that lead to clarifying what others need to expect from these circles, which is nothing to be concerned about. Or, it could be a sign that these tensions are not going through governance for resolution, and are instead getting resolved through a shadow power structure with implicit agreements — if that’s happening, there’s an opportunity to redirect more into the governance process to set more explicit agreements and expectations.

Remember, the purpose is to identify Holacracy sustainability issues –NOT improve the organization’s structure. Your organization’s governance isn’t anything we need to optimize or improve just for the sake of improving. Unlike a conventional org chart, no one is responsible for designing the governance — governance is organic. It’s the result of many many many people processing many many many specific tensions over lots and lots and lots of time. All governance is imperfect and no one should convey that it should be.

Read “Introducing the Holacracy Practitioner Guide” to find more articles.

To learn more about self-management, join a community of pioneers and check out our e-courses → Self-Management Accelerator