A Facilitator’s Mental Checklist for Tactical Meetings

For many Facilitators, the complexity is overwhelming and they end up doing too much or too little.

For many Facilitators, the complexity is overwhelming and they end up doing too much or too little.

Since there’s nothing special about the tactical meeting (i.e. you can do anything outside a tactical meeting that you can do inside of a meeting), the tactical meeting is a microcosm of the whole practice. Anything and everything can come up. For most Facilitators, the complexity is overwhelming. There’s just too much going on.

In response, Facilitators seem to think “I’ll just do my best to deal with whatever comes up.” And while doing one’s best is laudable, it’s not very clear or concrete, which means it’s actually hard to achieve. The result? Facilitators either do too much or too little.

A Facilitator who is doing too much is looking out for everything is constantly interrupting the process and slowing things down. They also get tired. That kind of vigilance has a price. Before long, they become so exhausted they actually become too passive and start justifying their lack of involvement. “Hey, I don’t need to solve anyone’s tension, right?” “Hey, this is an experienced group. They know what they’re doing.”

But there’s a middle ground between “I need to address every issue,” and “I don’t need to be involved.” Because while there’s an almost infinite variety of possible issues and coaching points, I recommend you focus on these five. It’s a sort of mental checklist to help guide you.

Note: I want to be really clear that these aren’t the only things you should ever worry about. My point is that as the elected Facilitator, you should practice these five moves in each tactical meeting you facilitate, and not to overly concern yourself with other things until you’re pretty good at doing these. If you get these down, you’ll not only be a better facilitator, but it‘ll be easier too.

And the sooner the better really. If processing an item is taking too long, just come back to, “Is this helping you?” or “Did you get what you needed?” and try to close the item as quickly as possible.

Since the Facilitator can prioritize items, you can ask the group, “Anyone have a quick item?” And while I’d normally avoid changing the order for a circle’s very first meeting because it adds complication to an already complicated situation, it works well with more experienced groups. The other situation when prioritizing helps is when you’ve done a few time-consuming or complex items; that might be a good time to see if any of the remaining items could be done quickly.

And if every item seems complicated, just bring your own item as Facilitator to demonstrate how you can process it quickly; e.g. just share some info, make it clear you’re making space for questions or reactions, and move on. Role-modeling this can be very powerful and you don’t need to cross your fingers that you’ll have a chance to do it. You can just do it.

Lastly, if an item is taking a long time to process, consider that you may be over-coaching, and be willing to drop an important coaching point for the sake of speed. It’s usually better to wave the white flag and look for another opportunity to revisit the issue, or just bring your own agenda item (e.g. “What I need here is to go back to that scheduling issue Stephen was talking about because there’s something about Holacracy I want to explain.”)

For people experiencing their first tactical meeting, Holacracy = the meeting. In other words, people are really asking themselves, “Can I trust this process? Will this work for me?” And they should. They’ve been asked to jump in and try something without fully understanding it and they just want to get oriented. So, processing an item quickly, at least one, demonstrates that “Holacracy” can be as effective as a normal meeting. Which is, after all, what they’re comparing it to.

A facilitator must proactively scan for opportunities because if they’re not careful, they could easily end up over-facilitating every single item. And even if you’re technically accurate in everything you do, you’ll likely increase fear and concern. In this sense, the medium is the message.

Processing items should generally be quick, but it takes practice. For a new person, or a new group especially, that’s hard to believe. Processing at least one item quickly gives you at least one opportunity to show the process doesn’t necessarily require a lot of new and complex rules or language. Plus, it’s a helpful reminder to you as the Facilitator to keep things moving.

Involving the Secretary is obviously critical because they’re the ones capturing the outputs, so give the Secretary a head’s up about your intentions. “As Secretary, your job today is to capture as many outputs as you can. You want to capture any next-action or project someone says they’re going to take, and I’ll be here to help.” Give them a license to capture first and revise later. They’ll still look to you for direction, but it’s a good idea to set some expectations.

Novice participants are usually happy to capture something they might not normally capture. After all, this is a new type of meeting and they’re usually willing to learn. As Facilitator, make this easier by saying things like, “OK, I heard you were going to send John that email, so for the sake of this exercise, let’s capture that as a next-action.”

If someone has already been through some tactical meetings they’ll have an implicit sense of what should be captured as an output versus what should be left out. That’s fine. Capture it anyway. The resistance to capturing outputs is never about trying to hide the information, it’s usually because it seems to take too much time. But don’t save time by skipping the capture step. Instead, save time by processing some items quickly (point #1) and working with your Secretary. That is, hold yourself to the discipline of capturing all the outputs you can, because that, in turn, and over time, will actually make you faster.

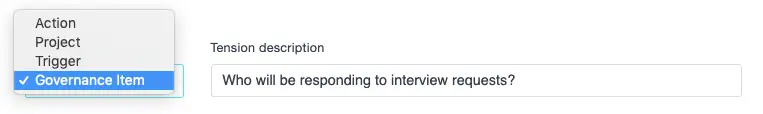

The key things to capture are any next-actions, projects, and governance tensions. You don’t need to capture 1) decisions that were made, or 2) information that was shared.

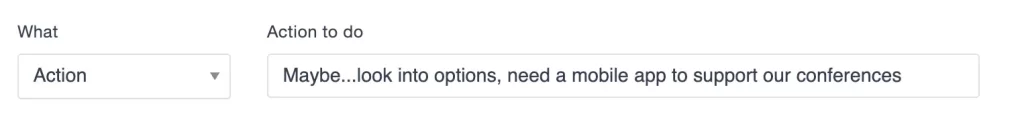

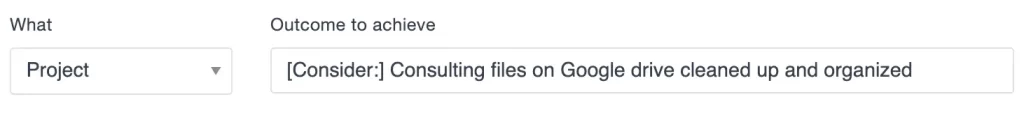

Finally, even if a role-filler is absent from the meeting, requests can still be captured. You can explain that GlassFrog records the outputs from the meeting and sends everyone an email, so capturing items brings some transparency to the proceedings. And since the project or action hasn’t been accepted by the role-filler, I recommend contextualizing the output, which they will see in their notification, by placing a “[Consider:]…” at the front (see example below).

Much like #1, the purpose of doing this is to demonstrate something about the meeting process itself. Specifically: it gets things done. Having lots of outputs at the end gives participants a visual artifact of what was accomplished. It makes the meeting feel substantive.

The second reason to do this is because outputs are anchors. As Facilitator, they give you some ground to stand on. And I don’t just mean as a record of what happened after-the-fact. I mean it as a way to help you process the item. Too often facilitators try to figure everything out FIRST, and once it’s all perfectly understood by everyone, then encourage the Secretary to capture something. At which point they basically have to revisit every…single…point…all…over…again. It’s crazy and unnecessary.

If you hear someone wanting something to happen (i.e. an outcome = a project), you don’t need to figure out the role first. No. Just have the Secretary capture the request in the text field. Now, with it roughly captured, GlassFrog’s drop-down options guide you to select for “Role,” and “Person.” Isn’t that nice?

Trying to capture lots of outputs will also help you process items more easily. Because really, the tactical meeting is just about moving things one-step forward. We aren’t necessarily solving these issues. If something is still unclear and time is getting tight, capturing a specific next-action (e.g. schedule a meeting) for a specific person (e.g. Wayne) helps release pressure. It makes it much easier to move on when the item-owner can see a tangible step forward.

This is also why it helps to be transparent about (and adjust to) the time you’re working with. If you have 10 agenda items and 60 minutes, let everyone know, “That’s 6 mins per item.” If participants are clear on their constraints, they’ll be more likely to self-discipline which just helps you get through more stuff more quickly.

There is almost no way a circle’s initial structure captures everything currently happening. So, if you can’t find a gap in their governance, it’s probably because you’re not looking hard enough. So, look for an excuse to highlight a gap, capture it as an output, AND show them that they can still deal with it operationally (though without any right to expect anyone else to do something).

To really appreciate the clarity Holacracy practice can provide, participants need to trust their own governance. They need to understand it and lean on it. Let me say that again. THEY need to understand it. A Facilitator can’t care about it for them.

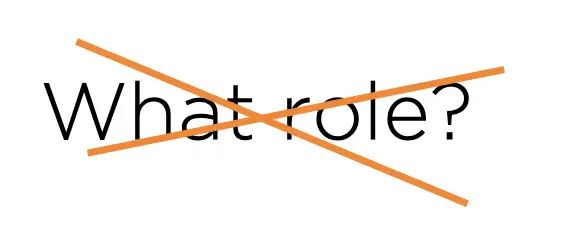

And the worst way to find gaps is to ask the question, “What role?” More often than not, people don’t hear a clarifying question. They hear judgment. If you only ask, “What role?” you’re sending the message that they should know the role and that the records should be comprehensive enough to have every role. But neither of those are true. Especially at the beginning.

Knowing the specifically defined role name isn’t a requirement to begin processing an item. How could it be? There are likely tons of gaps. So, instead of asking, “What role?” ask, “What role?…and it’s OK if you don’t know.” You want to make it very easy to identify gaps. Here are some others:

To effectively use Holacracy, practitioners must see their governance as two things; 1) an evolving structure that’s never quite perfect (i.e. it can change), and 2) as the current, agreed-upon set of expectations, restrictions, and authorities we’re all following (i.e. it’s official). Finding gaps and showing participants how to deal with them actually communicates this subtle and important message for you.

The second reason this is important is more practical. You need material for their first governance meeting. And the meatier the agenda item, the better the learning. So, don’t just hope that they bring good stuff to governance (at the beginning the distinction is usually fuzzy), help them out by identifying issues during the tactical that they can effectively resolve through governance.

This question is fundamental to good Holacracy practice. Sure, it’s doesn’t roll off the tongue, but that’s why it’s valuable. It helps breaks the pattern of pathological agreement. It makes you stop. And think. Not just robotically respond, “Yeah sure.”

As Facilitator, saying the whole sentence is critical. Using shorthand (e.g. “Are you OK with this?”) isn’t the worst thing in the world, because the language can easily feel overbearing and mechanical if you don’t have multiple ways of getting to the same information, but at some point, at least ONCE, pause and draw everyone’s attention to the specific question above. Say it with me, “In your interpretation, does it serve your role’s purpose or accountabilities to do that?”

I sometimes start by saying, “The question to ask yourself is…in your interpretation, does it serve your role’s purpose or…etc.” because, well, it’s true. Any question you ask as Facilitator is also a question a good practitioner asks themselves. Remember, anything that’s useful inside a tactical meeting is also useful outside of a tactical meeting. A good Facilitator knows this and goes about transferring their knowledge and experience of effective practice rather than trying to keep it all inside their own head. And again, you don’t have to worry about how to do that; I just told you: At least once, ask someone, “In your interpretation, does it serve your purpose or accountabilities to do that?”

This phrase highlights two monumental shifts. First, the phrase “In your interpretation…” cannot be overvalued. Sometimes, I take special care to gesture and verbally emphasize, “…YOUR interpretation.” Because according to the constitution, each individual has the right (and responsibility) to use their own interpretation.

The second shift is towards orienting one’s interpretation to an explicit set of expectations (i.e. governance) rather than orienting based on abstract principles, personal preferences, or office politics. So, it’s not just that anyone can interpret anything however they wish — it’s that anyone can interpret what has already been defined at the group-level.

Of course, language always comes down to individual interpretation, but through the governance process, the circle has a way to encourage or limit those interpretations. This is an important and subtle message which you can’t meaningfully explain conceptually. Thankfully, you don’t have to. Just look for a chance to ask someone the question, “In your interpretation, does it serve your role’s purpose or accountabilities to do that?” and the message has been sent.

Again, each part of the prompt is important, so at least once, don’t simplify or summarize it. Just say the long, awkward sentence as it is. If you’re like me, you’ll have to rehearse it, but it’s worth practicing because the awkward phrasing is what makes it effective.

I’ve seen two variations on this. The first places emphasis on making them feel the tension inherent with having to own one’s authority. That is, uncomfortable.

It sounds like this, “YOU have the full authority to take ANY action or make ANY decision to serve your role as long as it doesn’t break an explicit rule…so what do YOU need to make YOUR decision…[dramatic pause]?” And you just keep your focus on them until they say something. I love it. I really do. It’s very easy to dismiss how radical a shift Holacracy practice can be and taking even small steps outside of the nest will be challenging. So, we will all need lots of support, but we also need some nudging.

The second variation is less tension-generating. It’s a little softer and maybe a little looser. It sounds like this, “Ah! It sounds like you’re wanting to hear some thoughts and reactions from others, correct? If so, that’s great! Just remember you have the full authority to take any action or make any decision to serve your role as long as it doesn’t break an explicit rule.” You still need to say the whole thing, but you needn’t always make them squirm to get the point across.

Although it’s never explicitly stated in the Holacracy constitution, the rules are based upon the assumption that anything is allowed unless explicitly forbidden. And that’s the opposite of conventional organizations in which nothing is allowed unless explicitly permitted. If a practitioner doesn’t get that assumption, a lot of the rules aren’t going to make sense. But it can be awkward to explain conceptually, which is the main reason this prompt is important. You don’t have to explain it philosophically. Just remember to use the prompt and it will do the job for you.

Facilitating tactical meetings well requires two rare skills. First, you need to know when to help. Second, you need to know how to help. And if you’re a slow learner like me, then this will likely take years of practice (sorry, I should have asked if you wanted the bad news first).

The good news is that the curriculum needn’t be a mystery. Sure, there are lots of possible issues, and usually, multiple pathways to solve each one, but you don’t need to master them all to be effective. I wish I could say there was one single thing to remember to unlock the secrets of facilitating a tactical meeting, but five isn’t so bad, right?

Read “Introducing the Holacracy Practitioner’s Guide” to find more articles.

To learn more about self-management, join a community of pioneers and check out our e-courses → Self-Management Accelerator